A Costume Designer and His Archive

Back in June, Derron Cherry called me about fabric, key cards, and receipts. Specifically, he called me to talk about the fabric, key cards, and receipts he saved from working his latest gig. We used to work together at Tyler Perry Studios, but now I’m his archivist, so these days we talk less about continuity, measurements, and manpower and more about these small tidbits of the story he tells in his life as a costume designer, fashion designer, and stylist. As his archivist, I tell him to take these tidbits seriously. They are the physical remains of intangible creative decisions. In Derron’s case, his creative decisions are especially worth preserving, because, after all, they are the stuff of freedom, and in this case his latest gig—the BET Awards.

For this awards show, Derron styled two of the actresses from the BET+ show, SISTAS—one of the shows he designs at Tyler Perry Studios. He is one of two resident costume designers at Tyler Perry Studios, or what locals call TPS. He started as a tailor in 2016 on the television drama The Haves and Have Nots and after five years has worked his way up to costume designer in 2021. In the fast-paced, improvisational, and very Black production culture of TPS, he learned to work quickly and efficiently and by May 2022 was designing three shows simultaneously, including his first stage play, Poor Man, Rich Soul. Today, his filmography includes many TPS productions as well as First Wives Club, Cobra Kai, and The Banker.

Cherry inherited First Wives Club in time for its upcoming third season. Of the challenges of a new designer, he says, “I just express the characters, deliver the look, focus on casting, and use the situation as parameters.” After all, that is exactly what he did when he debuted as the designer for Tyler Perry’s SISTAS in 2021. Although different stories, directors, and production teams, the challenges are similar. Making Black women who are facing systemic issues related to racism, socioeconomics, and gender prejudice feel beautiful and strong in front of a harsh lens that constantly renders them invisible or hypervisible. While all stunning, these women are not traditional Hollywood fare, which sometimes makes the yardstick of talent violent, troubling, and destructive to one’s self-confidence, self-esteem and self-image.

The Catacombs of “Drip”

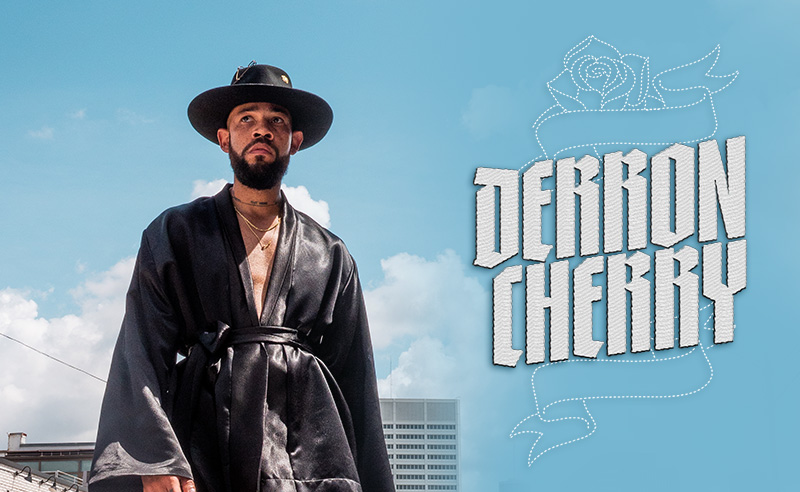

“Yo Bro, you drippin,” a young man says evenly as if Derron carelessly dropped something….wet. As I looked around the sidewalk to see if I could help my dear friend find what he dropped (or dripped) I heard Derron respond, “Yo bro, thanks.” Of course, “the drip” wasn’t a bodily reaction to the Georgia sun beating down from above, it was coming from underneath his clothes. The way he wore a combination of colors, cuts, and fabrics on his very long frame gave him the effect of looking hot, perspire-y, or as some would say, “drippy.” Derron does not design menswear, but when he appears as BEEOMBI he attracts the same amount of attention accorded to the girls of BEEOMBI, his celebrity clientele. I’ve never heard so many men compliment a brother on his clothes; it is pretty cinematic.

The BEEOMBI aesthetic matches the intensity of his image. With a perforated line tatted across his neck, he places his fate into the hands of onlookers and instructs them to “cut here.” Derron presents a bit carnivalesque in a medieval sort of way. Francesca Granata’s theories of fashion as a Bakhtinian space and a realm of the grotesque offers Derron’s uncanny image a soft place to land. His body as an anarchic space temporarily suspended from all order and authority, like the anthropomorphic figures in the decorated grottos of Italy, provokes new ideas and possibilities. From the lower regions of our time-space continuum, the grotesque body is a site of liminality, as well as border-crossing which undermines social norms and rigid definitions of beauty calling forth new identities. Interestingly, Giorgio Vasari, the 16th century art historian, describes the very sophisticated process of beautifying grottos by natural means of petrification and incrustation in order to create….yes: the drip. No wonder cisgender heterosexual men feel safe to stare and compliment his sartorial effects. He’s drippin’ like the beauty of an ancient Italian cave.

A beautiful bouquet of flowers that escapes his collar, up the side of his bald head, also looks like the moment a flower toss smacked the back of his head. As if he were trying to discreetly exit the wedding festivities of his latest bridal client. That’s Derron. As for the BEEOMBI girl, the runaway bride is wearing solid bold colors and creating dramatic lines. There is no husband, but she is escorted and therefore the banshee of the ball. Together, Derron/BEEOMBI creates an experience for everyone in the room. Depending on one’s proximity, he, she, or they are cast into the role of a supporting actor or minor player to star power. The women he dresses look like superheroes and villains at the same time, and he is the master craftsman. [Yes, I have been styled by him!] It is quite the lewk to conquer the ravines of Atlanta.

His Story and His Documents

When Derron arrived by way of Selma (Dir. Ava Duvernay, 2014), it might have had something to do with Atlanta’s strong gravitational pull from early days as “Terminus,” the transportation destination for the North and West. Derron grew up in St. Louis with his mother and sister, but probably spent most nights sharing a twin-sized bed with his best friend, Naja. Having learned his craft from his mother, he began specializing in dressmaking early. Looking at pictures of her, I see their striking resemblance and that their relationship was close. His light skin tone, freckles, and unflinching eyes peer out from beneath a doobie and a finely tailored men’s suit. And yes, his mother snatched in a suit.

And she was his first archivist. Takes one to know one. From elementary school report cards to college acceptance letters, these documents are neatly preserved between the pages of large old photo albums—the ones with the sticky surface and the thick plastic that pierced the sonic landscape when you peeled it back. Even though he reports to only have gone to class 60 percent of the time, his grades show that he was in the Honor Society, made the honor roll, and achieved very high grades. This guy has been a secret overachiever his whole life. No wonder she kept everything.

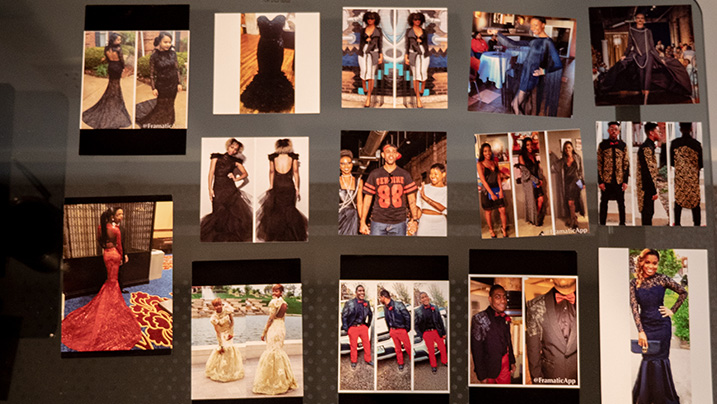

In 2006, the 6’5” designer was crowned Prom King at University City High School. After finishing high school, he honed his craft as the “Promdressmaker” for young women all around his city. Questions I wished I asked: how many dresses did he make for that prom season; did he make all the dresses of the throne; what about the Queen? Always a popular guy, his first fashion show was while he was still in high school. Throughout his archive, I can see how important his friends are to him. In one photo, he shows me a friend who has been a part of every single one of his fashion shows; on neatly folded paper, a friend writes to him about where she went wrong from a detention center; another friend, Twiggy, has been his assistant for over 20 years.

The Selma Moment

Derron describes Selma (Dir. Ava Duvernay, 2014) as one of the turning points of his career. As his first major film, he got a crash course in filmmaking and tailoring for the camera. Interestingly, like many of his jobs, he did not apply for it. He was hired shortly after meeting the well-known tailor, Kevin Mayes, who worked as the head tailor on the film. Selma became the impetus to his relocation to Atlanta and his pursuit of costume design. In 2015, Derron became a local.

Last fall, Ruth E. Carter: Afrofuturism in Costume Design was one of the most visited exhibitions in the gallery spaces of SCAD FASH, SCAD’s fashion and film museum. The legendary costume designer’s first solo show was a hit amongst film aficionados, Black history nerds, Wakandans, ATLiens, etc. The most exciting part was the very fact of the archive. The designer collected, preserved, and helped display costumes from movies School Daze (1988), Do the Right Thing (1989), Malcolm X (1992), Amistad (1997), Shaft (2000), Black Panther (2018), Dolemite Is My Name (2019), and Coming 2 America (2021) for our casual perusal, research, and inspiration. Rich fodder for our ever-expanding, backward-looking, forward-thriving Sankofa moment.

Upon entering the main gallery space I encountered a Radio Raheem-dressed mannequin complete with a set of love and hate rings on its outstretched knuckles. To the left of the Do the Right Thing exhibit, a few wall cases displayed small archival materials ranging from early sketches, color and textile swatches, digital illustrations, and reference materials from her film projects. Amongst these materials was a small 4×6 snapshot of “final touches” on the set of Selma. In the center of the photo, a little girl in a blue texturized, mid-calf, 1960s, church dress with cap sleeve bow ties stood like a mannequin with her arms raised to assist the design process. With her head tilted downward, she focused on Ms. Carter’s hands tying the matching belt at her waist. Just like the navy and white embroidered slip peeking from beneath the slightly diaphanous fabric, a 20-something Derron can be seen fixing the apical moment on the young girl’s frame. With a piece of the dress’s blue fabric in one hand, he zeros in on the backside of the white textured hat that matched the pattern of embossing on her dress. Derron’s raised elbow created an isosceles symmetry with Carter and other crew as they shared intensity at different levels focusing on the young girl’s costume.

The Catacombs of Atlanta

Atlanta is a rich broth; you can cook with it or be cooked in it. The key is understanding that it all starts with a script. Whether it’s film, tv, these virtual streets, or this hot pavement, it is all a performance and we are all playing a part in it. And this is where costumes enter. Costumes are the space between the stories that live inside of us and are a physical manifestation of how the environment scripts us. So for the designer, the questions are always: who is this person in this space and time; what does that feel like; and what does that look like?

During a moment of deep reflection, Derron says, “I’m more inspired to know how easily attainable wealth is. I’ve always wanted wealth for the sake of experience and for the sake of being able to create that experience for other people. Every time I go to Africa, I see that it looks much richer than the land that I come from in every way. This [The United States] is the land of money, but Africa appears wealthier in spirit, roots, and agriculture…the greens are greener, you know, and I mean, like seeing just the richness in itself is just an inspiration. I think traveling just opens the mind in a different way when you get to see and connect with people from a different part of the planet. And you realize that you’re just really all human on a basic level, just decorated differently.”

It is no secret that Africa occupies a special place in the hearts of Black America. As a site of loss and identity, many of us find the pilgrimage life changing and insightful. On his most recent trip to the continent, he experienced flight cancellations, delays, and loss of luggage. He arrived in Mozambique metaphorically naked. His clothes that had become his self-expression, his armor, his protection, and his script were lost. For a sartorialist, this trip added to his perspective in a way that only the universe could have arranged.

Preserving the Drip

As a performance archivist, I spend most of my time mattering. No, I don’t mean making myself significant to other people (although that’s fun too); I mean building mechanisms to create access to the wealth of knowledge found in our bodies—particularly Black bodies. If history relies on what is found in the archives, then I believe the preservation of our stories is the gateway to our freedom. So, while I am thinking about how to get to freedom through methods of archival science, Derron actually preserves freedom by creating what it looks like for the camera and constructing what it feels like in the streets.

Atlanta is a distinct mise-en-scene. Designing Atlanta, (the city and its inhabitants, not the show) involves an intimacy (and a car). Atlanta is down south, but it is not The South. It is not chitlins, hog mogs, and cheap cost of living. It is a metropolis, a mecca for all things DIY, CNN, CDC, TPS, MLK, and T&A. ATL is home to animation, music, and the tech industries, as well as popular attractions like The World of Coke, The Honda Band Battle, HBCUs, and Black culture. So when picturing Atlanta, it involves more than just what’s ITP. It is common to see the racks at Lenox Square Mall, Buckhead Station, Phipps Plaza, Perimeter Mall, and in Lil’ Five Points jam-packed with ATL’s most fashionable. But for the designer/stylist, visualizing the creativity that lives in Atlanta is alchemy. It requires using shops, labels, and textiles as mere ingredients to the stories that are created in these spaces.

Whether it’s the canary-yellow trench coat from Teyana Taylor’s homage to Michael Jackson in “Bare Wit Me,” the neon-yellow pant-suit worn by actress Mignon at the BET Awards, or Nia Long’s 1960’s daffodil yellow two-piece number in The Banker (2020), the fabric seems to provoke questions. Derron says that “freedom is in the midst of what you prayed for; resistance is creating, pressure, guidance, and a substitute for a lesson; and preservation is collecting memories in time for inspiration, history, and storytelling.”

He ended that June phone call talking about the significance of space in dreaming. He said, “I love architecture and just like really dope housing. When I was in L.A. just looking at the hills, I was like ‘I can’t wait to be up there.’ And then I get on the elevator to leave. I got all of my shit, my sewing machine, all of this and this guy gets on the elevator. And he’s like, ‘Who are you?’ And I said, ‘BEEOMBI. I am a costume designer, fashion designer, and stylist.’” We never know what may come from these tidbits. An anthropologist might be interested in high-end textiles being used in clothing in the summer of 2022; Derron’s biographer might need to re-create a map of locations frequented by celebrities; or a filmmaker might want to tell a story about post-pandemic Black success using receipts related to ceremonies of Black excellence. In any case, these tidbits are surely the counterfoil of freedom for the Black body in the catacombs of drip and here, they are preserved for you.