By: Carol Badaracco Padgett

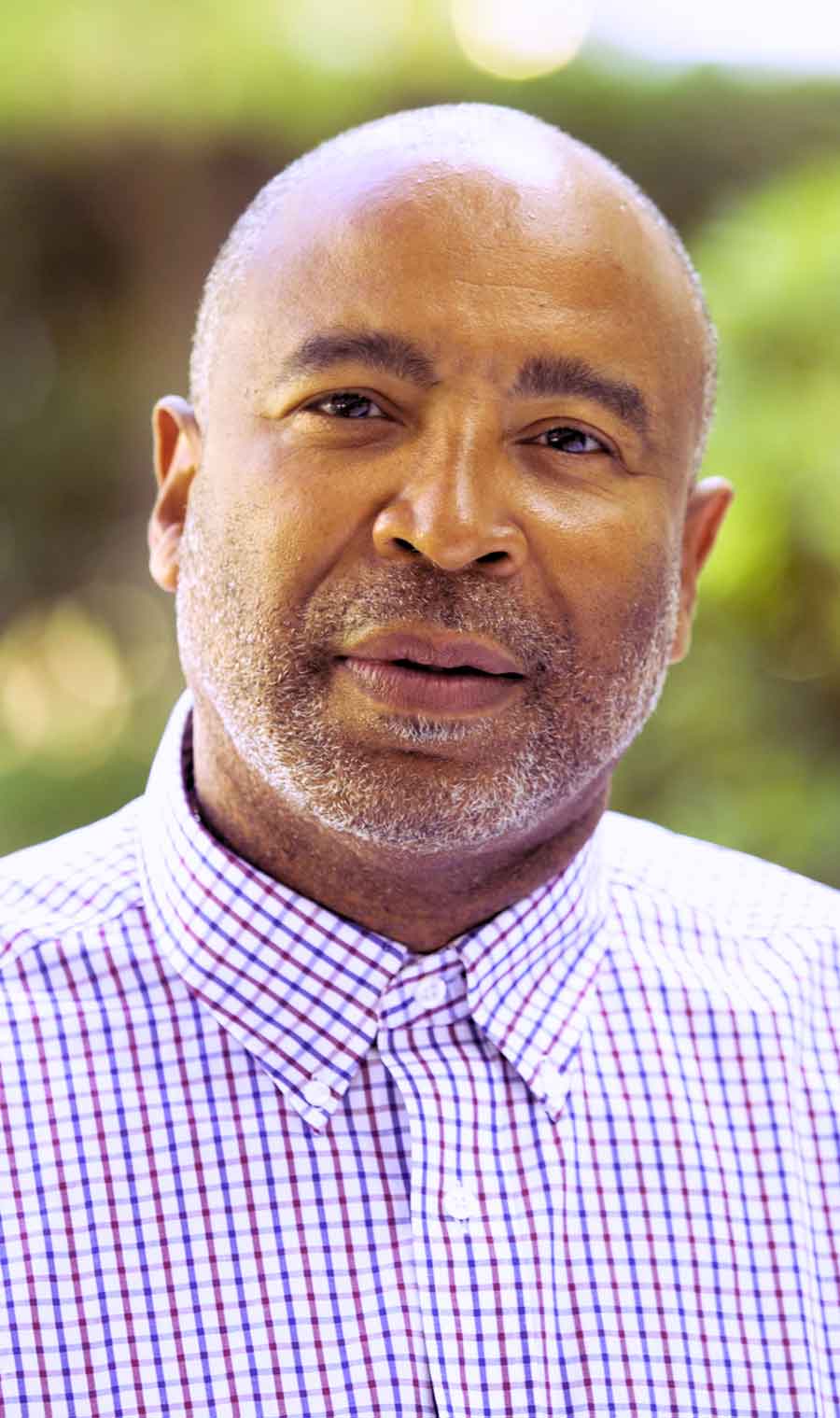

Barrett Dungy

“Atlanta was a music town then, not a film town.”

“Atlanta was a music town then, not a film town,” Barrett Dungy, the CEO of Urban Home Entertainment, remembers of nearly 20 years ago when he started out as a film distributor in the Big Peach, of all places.

Back then, even his lawyer told him he was crazy.

Undaunted, Dungy decided to take a plunge into the impossible film distribution business. With less than $3,500 and a boatload of determination, he has since distributed over 600 films and TV shows across the globe.

While the creative process of filmmaking is talked about a great deal, film distribution is not. And yet, it’s crucial—and essentially the vehicle that turns art into revenue, getting a film where it needs to be to generate dollars.

As such, film distribution can entail selling a film to as many platforms as possible, cinematic releases, and more. And to get the ball rolling, the film festival circuit is often where film distributors can be found, eyeing potential content (it’s always wise for content creators to have that IP copyrighted), and where directors who are looking for distribution, in turn, are eyeing a sound fit with a distributor who works in their film’s genre.

(While Urban Home Entertainment generally works with finished films, they also consider scripts or sometimes even pitch stacks submitted through their website, urbanhomeent.com.)

Among Dungy’s early film distribution clients was a relatively unknown young man, Tyler Perry, who was releasing a film (Diary of a Mad Black Woman) and wanted to simultaneously release a Gospel play onto DVD in retail stores.

“He wanted the play into the stores when the movie came out,” Dungy remembers. “That was the hardest job I’ve ever had in my whole life. Nobody knew who Tyler Perry was, and it was a play, and it was the film, and [film business] people said, ‘NO!’”

Dungy had some other titles in his stash of projects at the time, but still, everybody said NO!

“Then finally, I got a ‘maybe,’” the now seasoned film distributor states.

Lionsgate Films had the movie, Diary of a Mad Black Woman, and took on the DVD too, and it became the biggest selling DVD of that year, ushering in a new genre of live-action plays on DVD, Dungy says of the especially large deal for African American content.

At that point, the CEO adds, “I started to license a whole new genre for African Americans.”

“I prayed and said, ‘God, I’ll give it back to you, I promise.”

– Barrett Dungy

Dungy decided in the beginning, when he realized he’d worked his way into the role of film distributor, that he would always do one very simple and critically important thing that his dad taught him: always answer his phone.

“I prayed and said, ‘God, I’ll give it back to you, I promise. And I’ll always answer my phone,” Dungy states. “God had a sense of humor and made me a distributor. I had little to no money, and you needed millions to do this. And now, 350 films later, here I am.”

He says of the method to his madness, “Meet viewers where they are and tempt them where you want them to go. Most of the movies I distribute are a cautionary tale. They transform and educate.”

Once his distribution business was sailing full steam ahead, Dungy’s role in the film and TV industry began to expand—into somewhat of a mentor to young filmmakers.

“I understood [at the time] that the market was flooded with African American films that were mostly drugs and guns,” he states. “I said I’m not picking it up. That’s not gonna be me. I wanted to bring in all sorts of African American films of family, faith, comedies, and romance. So I did.”

He also gave the filmmakers who were creating largely violent content the opportunity to tell some of the other stories they wanted to tell.

“Some of these filmmakers matured, and so did their vision,” Dungy says. “I gave an opportunity to these filmmakers, and they could look inside, into why [their message] is important, and we became trusted partners with the studios. And then our track record began to speak for itself.”

Today, Dungy distributes for major studios like Game Show Network and many others. And he finds that he has worked himself into identification with yet another genre: Urban, Latin, and LGBTQ content.

“I want to provide opportunities for every culture to have a shot at the American dream,” Dungy states. “I’ve become like a civil rights activist, and my job is to make sure everybody’s voice is heard—because that’s what the world looks like.”

There’s no better person to herald the urban niche, in fact, because it’s a place Dungy intrinsically knows firsthand as a Black man living in a city known for its rich diversity.

From day one, “I rarely saw people who look like me on the other side of the phone call,” the distributor notes of the very discrepancy that has become one of his greatest strengths.

“I understand the struggle of minority filmmakers—struggling and trying to get their story out there,” Dungy states. “There has to be somebody on the other side [of the conversation] to listen and give them the opportunity to tell their story.”

Sometimes, the best medicine in this world is comedy, and Dungy supports that genre and distributes it too.

From working with Tyler Perry to comedians Gary Owen and Kevin Hart, the Urban Home Entertainment founder realized he was amassing a growing catalog of comedy content. So he created a label especially for the genre: The Ruckus Comedy, which gave a shot to Little Rel’s first standup and now handles the shows of Jamie Foxx, Laffapalooza, and Gotham Comedy Live.

Looking back at his early work with Perry, Owen, and Hart, Dungy muses, “How many other people are undiscovered like that? I can be giving them their first opportunity. If it’s not me, who will give them the opportunity?”

Of his work with comedians through The Ruckus Comedy, Dungy feels blessed to have had their backs during the pandemic, where his work helped get standup comedy in front of homebound viewers.

“I’m proud of it that during COVID we were delivering checks and [comedians] now had residual income,” he smiles.

The distributor circles around to the latest mission he feels empowered to fulfill: helping marginalized filmmakers get their voices heard and their stories told—and in the process, helping viewers. “Other people need to see it. They need to see themselves in the picture,” Dungy says. “And my job is to make that happen.”