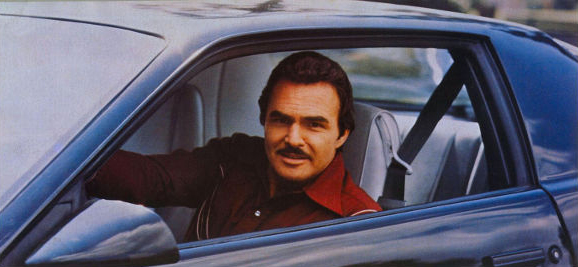

Say what you will about Burton Leon Reynolds, Jr. (February 11, 1986 – September 6, 2018), but if not for the highly ambitious boy from Lansing, Mich., it is entirely plausible that neither the magazine you’re reading, nor the booming Georgia film industry from which many of us make our livings, would exist.

Was he purportedly, at least for a time, emblematic of pre-#MeToo Hollywood’s most dismal behavior? It’s been alleged. (Repeatedly).

Was he a mercurial man whose ego could render him ‘prickly’ to the point of offense? It too has been alleged. (Although who among us hasn’t been guilty of this without the entire world watching)?

But was Burt also somehow magnetically, inexplicably, outwardly in love with the State of Georgia at large? You’re damn straight.

In fact, he gushed endlessly about us to any news outlet that would afford him the airtime, and was still doing so right up until his passing on Sept. 6. “Every time anybody wants to make a movie with me, I ask, ‘Can we shoot it in Georgia?’…” he told myself and a roomful of fellow journalists during a press conference last November while out promoting one of his final projects, The Last Movie Star (2017), a pseudo-life-meets-art film about a washed-up Hollywood legend who bristles at the fact that his heyday has faded over the horizon. “I just love coming here. I love the people here. That’s what I mean, that’s what it’s about.”

“Every time anybody wants to make a movie with me, I ask,

‘Can we shoot it in Georgia?’…”

In fact, he gushed endlessly about us to any news outlet that would afford him the airtime, and was still doing so right up until his passing on Sept. 6. “Every time anybody wants to make a movie with me, I ask, ‘Can we shoot it in Georgia?’…” he told myself and a roomful of fellow journalists during a press conference last November while out promoting one of his final projects, The Last Movie Star (2017), a pseudo-life-meets-art film about a washed-up Hollywood legend who bristles at the fact that his heyday has faded over the horizon. “I just love coming here. I love the people here. That’s what I mean, that’s what it’s about.”

Touché, Mr. Reynolds. We so deeply appreciate you, sir, for both your endorsement and your recognition of what we could become.

On this note, let’s make it a point to remind ourselves, particularly for those of us who grew up here: Outside of music, the Georgia of the early 1970s was a veritable desert for the arts before Burt Reynolds arrived. Deliverance (1972) put us on the map. The Longest Yard (1974) ran with the baton. Then Smokey and the Bandit (1977) more or less blew the doors off—better yet, down. And in the decades since, the lot of us have staggered through them with little homage to the godfathers—Reynolds, Ed Spivia, et al— who mustered the chutzpah to mine our potential.

When the ghost of Jim Crow had barely been shooed off our back porch, when the headlines from an abysmal, humiliating pushback against Civil Rights had hardly begun to fade from the front page, Burt and a handful of other filmmaking elites saw past our darkest demons and helped usher in a new era of light. Today, this forward-looking act of grace has blossomed into a revolutionary reshaping of Georgia’s image. We are now a place where arts and culture, as well as the talent that it takes to cement and profligate both, are revered as first class.

With the six highly successful films he made here during the ’70s—Smokey and the Bandit alone raked in $126.73 million at the box office—Burton Leon Reynolds, Jr., son of Fern and Burton, Sr., certainly delivered on his notion to spearhead a new wave of motion pictures made, as he put it, “in the South, about the South, and for the South.” Little did he know, but how proud he clearly was, of the way in which we piggybacked his vision and parlayed it into the nearly $10 billion powerhouse that Georgia’s film industry boasts today, some 36 years after Deliverance debuted in theaters nationwide.

As his life so beautifully illustrated, who we are should never be narrowed to our occasional lapses in judgment. Our lives amount to so much more than our momentary fits of ugliness, especially when we leave behind a legacy that exponentially improves the lives of so many.

Godspeed, Bandit. Wherever you are, I hope there’s a fully gassed Trans-Am and a CB radio tuned to eternity.