“It’s like a black mecca. Like Black Hollywood,” says Amber L.N. Bournett, one half of the Atlanta-based art film duo, House of June.

You have Hollywood and you have Black Hollywood in Atlanta.” We—Bournett, myself, and the duo’s other half, Ebony Blanding—have been speaking for more than an hour. The quirky Candler Park cafe we’re in will be closing soon, and both women are coming off a full shift at their day jobs. But Blanding and Bournett have plenty stories to tell about being minority filmmakers in Atlanta. Their work has been featured at the Sundance Film Festival, and their short film The Grey Area was featured in the Atlanta Film Festival’s 2015 New Mavericks series.

Since the city’s rise to prominence in the nation’s film industry, Atlanta has been given many nicknames. Hollywood of the South. Country-fried Y’allywood. The clunky A-T-L-wood. But in conjunction with (or in contrast to) all of these, is Black Hollywood: a mecca for minorities looking to break into film and television production.

Building Black Hollywood

In 2008, Governor Sonny Perdue signed Georgia’s tax incentive into law, granting any film or television project that spends $500,000 or more on productions in Georgia a 20 percent tax break, with an additional 10 percent break for projects that put the state’s logo at the end of their credits. Though the incentive is often credited with Atlanta’s production industry taking off, insiders know a strong film community existed here long before the tax breaks went into effect.

Makeup artist Patrice Coleman came to Atlanta to attend Spelman College and has been in the industry for nearly 40 years. She’s a member of the relatively small community of professionals who have been in Atlanta since before the boom. “The thing that stood out to me about Atlanta from the very beginning was that Atlanta was very supportive of black entrepreneurship,” Coleman says. “There was a strong academic community, which included a good number of universities and prestigious HBCUs [historically black colleges and universities].”

Coleman says the state’s affordability, climate, and history contributed to a well-balanced quality of life for industry folks. “We’ve always had a pretty solid film community. Even though a lot of people think it didn’t happen until they got here, which is funny to me,” she says. “It’s kind of like Columbus discovering America. We really were doing okay before.”

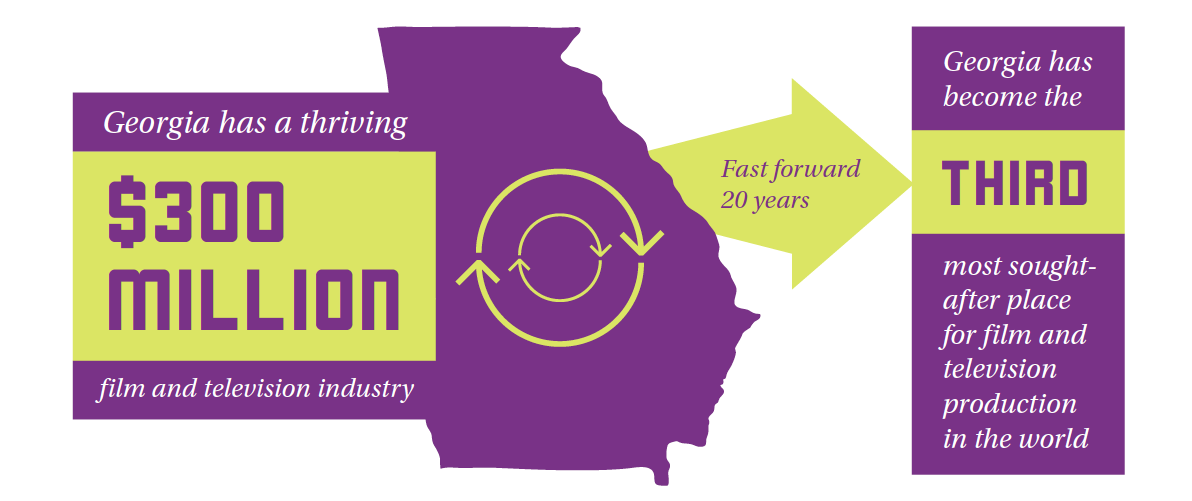

In a YouTube video of former Mayor Maynard H. Jackson Jr. establishing the Atlanta Commission on Arts and Entertainment in 1992, the mayor acknowledges the city’s rising film industry. “We have a great, great potential here,” he booms. “The background is that Georgia has a thriving $300 million film and television industry, and we’re well on our way to becoming the third largest entertainment center in the United States.” Fast forward 20 years, and Georgia has indeed become the third most sought-after place for film and television production in the world.

Production supervisor and Great Fortune Films founder Latisha Fortune (The Blind Side, The End Again) and Bobbcat Films EVP Angi Bones (The Negotiator, The Antoine Fisher Story, House of Payne) remember pre-incentive Atlanta as a place of greater opportunity where people could break into the industry on the ground floor. “When I came to Atlanta in 2005, Atlanta embraced me,” Fortune says. “New York was already established, and it was very difficult to get into the circulation, whereas in Atlanta, there was an opportunity basically for everyone.”

Bones came to Atlanta from Los Angeles in 2002 when she was an extras casting director and DGA assistant director. She noticed immediately that there were maybe five films in production but only four DGA ADs in town, so she sought to fill the empty space. It worked. But Bones’ decision to move to Atlanta full-time was influenced largely by the heavy minority presence on sets here. She had never seen so many people of color working on one set at one time back in L.A.

“Living in Los Angeles, I may have worked with maybe one black teamster and maybe one Hispanic teamster. But when I came here, there were black teamsters, there were black female teamsters, there were black-owned production companies, black directors, black producers,” Bones says. “It was just a hub of people of color that were doing things.”

“It was just a hub of people of color that were doing things.”

For those born and raised in Atlanta, people of color doing big things isn’t out of the ordinary. They grew up knowing they were in the birthplace of the Civil Rights Movement. Martin Luther King Jr.’s childhood home was less than two miles from the capitol. Location scout Jen Farris, who was born and raised in Southwest Atlanta, recalls the inspiration that comes with having black leaders who were respected across color lines and across the globe. “It’s unusual, from what other people tell me. It’s not unusual for me,” she says. “But to an African American little girl, that’s almost like seeing a female presidential candidate, so you look up to that. As a child, that has a big influence on your dream list.”

Atlanta’s can-do spirit and history of black entrepreneurship are what drew Bobbcat Films CEO and president Roger Bobb to the city. Bobb initially came here at acclaimed casting director Reuben Cannon’s request, to help direct Tyler Perry’s Diary of a Mad Black Woman. After years at Tyler Perry Studios, where he produced I Can Do Bad All By Myself, For Colored Girls, and over 200 episodes of House of Payne—the longest-running black sitcom in history—Bobb branched out on his own. Bobbcat Films conceives projects in-house and develops content others create. Like Tyler Perry, Bobb’s projects are deliberately for and about African Americans.

“You have a lot of African Americans who are [here] in other areas of business, who own their own businesses,” Bobb says. “Just that whole attitude of progressiveness is what convinced me to start my own company.”

When Color Matters, Or Doesn’t

“The movie industry… I can’t say that it sees color,” says Angi Bones. Alfeo Dixon, a DP whose resume includes The Yard and The Walking Dead, among many others, agrees. Apart from a comfort factor, there’s not much difference between being on a predominantly white set and an ethnically diverse set in Atlanta—or anywhere else—when it comes time for work to be done. “What’s the difference between going to a black surgeon versus a white surgeon?” Dixon asks.

Does it matter who does the work if it’s done well? Blanding and Bournett say no, but also yes, because a “good job” is not a set standard. The pair argues that when it comes to something like lighting, color does matter. African Americans are less likely to be lit well because they historically haven’t had significant roles on screen.

“You would be in the shadow. There would be no light reflecting off you significantly,” Bournett says, gesturing to me. “And that makes you focus on the other person in the screen, who was more than likely the main character, who was more than likely a white person.”